Refugia Newsletter #16 by Debra Rienstra: Alaska Edition

Refugia News: Alaska Edition

Ron and I just returned to Michigan after two weeks in Alaska, so if nothing I write today makes any sense, you can blame it on jet lag. We had originally planned our sojourn in the north country way back in 2019, but the trip got delayed twice because, you know, Covid.

Yes, we went on a cruise. Yes, I feel guilty about the carbon footprint and extravagance of the whole expedition. But doggone it, the cruise was wonderful. And our little adventure in the Great Land (the meaning of the Aleut word from which Alaska derives) gave me the chance to learn a lot and gather some observations for you about how climate change is--or actually isn't--talked about in the context of Alaska tourism.

Alaska is on the front lines of climate change. According to the Third National Climate Assessment, "Over the past 60 years, Alaska has warmed more than twice as rapidly as the rest of the United States, with state-wide average annual air temperature increasing by 3°F and average winter temperature by 6°F." Here's the science on why--basically "surface albedo feedback." This turbo-warming is resulting in a number of serious impacts: glacial melt and sea ice reduction, permafrost thawing, disruptions for all kinds of creatures, insect infestations, crop stress, and wildfires.

The mainstream tourism business, however, apparently keeps these alarming facts on the down-low. I listened carefully to the informational lectures on the ship and to the various tour guides on our land excursions. With a few key exceptions, I heard only mild references to a "warming climate." I suppose I shouldn't be surprised. Did I expect the cruise industry to change their motto to "Hurry! See it all now before it's gone!"?

And of course, since climate change is one of the most politicized issues we have going, it's not surprising that mainstream cruise lines and their ancillary tourism outfits are reluctant to "offend" anyone with stern discourse about the climate crisis.

On the train between Anchorage and Denali, someone asked about all these dead spruce trees, and our guide seemed a little embarrassed to tell us that what we were seeing was the result of climate change. He explained that the spruce bark beetle is thriving in warmer temperatures and thus killing off trees.

Alaska is complicated. It has a lot to lose as climate impacts worsen, but its modern economy is critically dependent of fossil fuel largesse, the military, and of course tourism. Indigenous peoples have lived in the region for at least 12,000 years, but with the onset of European exploration, Alaska's history became a tapestry of brutal resource extraction: furs, whaling, mining, logging, coal, oil. It's painful to hear all these complexities and abuses glossed over by your tour bus driver, who merrily gestures to Alaska's "rich cultural history."

"More Valuable Alive"

Conservation, on the other hand, is a theme more likely to resonate with a wide range of people. As we kayaked around Tatoosh Island, for instance, our guides made us feel like genuine heroes for coming on their excursion because, they assured us, by supporting this kind of tourism, we were also supporting conservation.

On our whale-watching excursion out of Juneau, the guide emphasized that tourism helps make wild creatures "more valuable alive than dead," which: yikes. But sure, yes.

Our guide at Denali National Park stressed the park's extremely limited tourist infrastructure (trails, campsites, etc.), which helps preserve the park as a wilderness "for future generations."

We did hear often about how important it is to preserve all these beautiful land- and sea-scapes for future generations. Those grandchildren are going to need places to visit! (Also, apparently the grandchildren will need jewelry stores. What is it with all the jewelry stores both on the ship and in the ports? I was never seized by the desire to buy jewelry on the trip, but perhaps jewelry-lust is a common side effect of traveling on cruise ships? Not sure.)

Anyway, it's good to hammer on the importance of conservation with tourists, but this does raise a foundational philosophical question: are bioregions and the creatures in them valuable only insofar as humans can go gawk at them? And pay money for the privilege?

Here Comes the Science

I thought about this question of value while soaking in the beautifully curated exhibits at the University of Alaska Fairbanks Museum of the North--which I highly recommend.

Among other things, the museum has a fantastic collection of prehistoric bones: a woolly mammoth skull! an ice-preserved prehistoric bull! a baby mastodon ... thing! Marveling at these emissaries from the past makes one ponder how this planet was full of creatures long before human beings turned up to ponder them (or hunt them). Those long-extinct creatures existed, I believe, for the delight of God, the sheer ecstasy of life in divine design. But the same can be said of all the whales and grizzlies and willow ptarmigans living their lives today, including the ones human beings never lay eyes on.

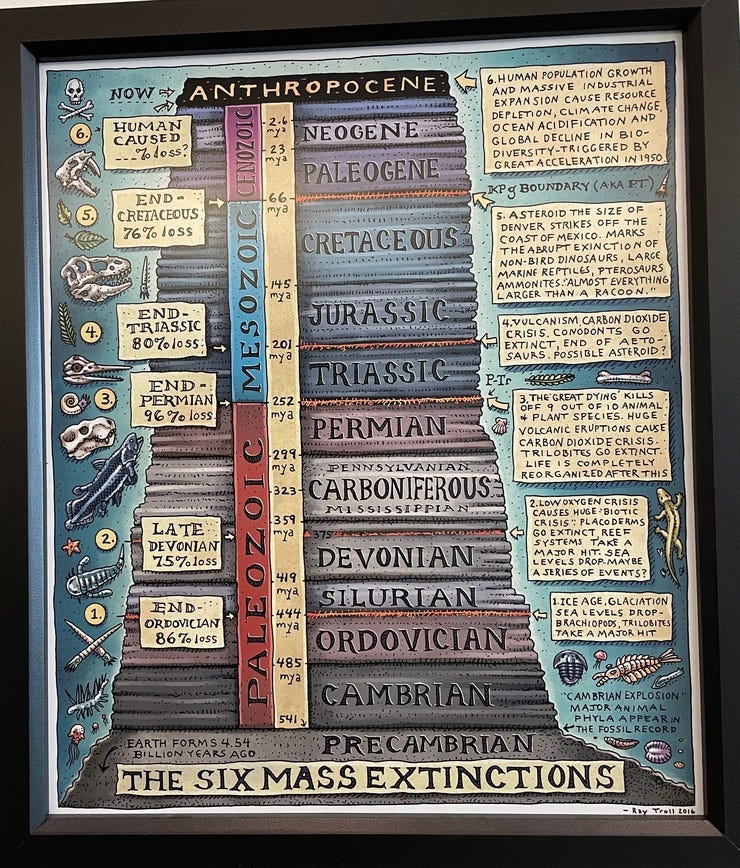

Since the Museum of the North is closely connected to University of Alaska researchers, the exhibits addressed the climate crisis more frankly and directly than we heard about on the touristy tours. Here's a cool chart created by Ketchikan-based artist Ray Troll, explaining the Six Mass Extinctions--that includes the current one in progress. Sobering.

I noted throughout our Alaska journey that the closer we got to science, the more we heard an honest account of the facts about climate change. While we cruised through Glacier Bay National Park, for instance, a park ranger came aboard and helpfully explained glacial geomorphology. She was not shy to lay out the statistics about melting glaciers. According to a recent study published in Nature (I looked this up later), Alaska’s melt rates are “among the highest on the planet.” We got to see this ourselves on the Mendenhall Glacier.

In Glacier Bay National Park and College Fjord, we admired the sheer size and power of the very few "surging" glaciers like the Margerie Glacier. That blue color is even more stunning in person.

Land Like Poetry

Naturally, I brought along some appropriate reading material for the trip: Barry Lopez's 1986 classic, Arctic Dreams. It's a masterful work of nonfiction writing both scientific and poetic, weaving together philosophical musings about place, harrowing histories of arctic exploration featuring salient examples of human bravery and utter folly, and absorbing life-dramas of migratory birds, narwhals, polar bears, and caribou. Here are a few of the passages I highlighted.

This one sums up Lopez's writerly striving to seek wider significance in his travels in the Arctic:

"The land is like poetry: it is inexplicably coherent, it is transcendent in its meaning, and it has the power to elevate a consideration of human life." (274)

Here's a reflection that helps me understand my own feelings of deep connection to the Michigan landscapes I write about in Refugia Faith:

"The complex feelings of affinity and self-assurance one feels with one's native place rarely develop again in another landscape." (255)

Finally, while considering indigenous people's deep connection with the land alongside the whole sweep of human civilization, Lopez writes:

"Have we come all this way, I wondered, only to be dismantled by our own technologies, to be betrayed by political connivance or the impersonal avarice of corporations." (40)

Now there's one to reflect on even more urgently today than in 1986.

Next Up: UK

As for feeling guilty about travel: I know that in the scheme of things my personal carbon footprint is small potatoes. And according to this website, the entire tourism industry contributes only (only?) 8% of the world's carbon emissions. (Can't verify that figure, sorry.) A lot about mainstream tourism is wasteful and carbon-intensive and eco-not-friendly, even if hotels want you to feel you're "doing your part" by using your towels more than once.

Still, a lot of people depend on the travel industry for their living and there's much to commend about getting out of our bubbles and coming in contact with other kinds of people and places. How to do it meaningfully, sustainably, and thoughtfully? I know there are good souls working on more sustainable travel options, but I don't know much about those initiatives yet. I'll try to find out more and get back to you.

Honestly, I don't love traveling. I hate planes and feeling cramped and living out of a suitcase, and I always miss home. So I'm almost sorry to tell you that we're turning right around and leaving again in a few days, this time for the UK, where I'll be presenting at an academic conference. Nothing to do with Refugia Faith or climate or anything; the conference is on the seventeenth-century poet George Herbert--one of my scholarly specialities. The conference has also been postponed twice because of Covid. Finally we get to do it!

Even though I'm not wild about packing up again, I'm not complaining. We're going to make the most of this opportunity, and I'll be sure to learn and notice and write down things that might be interesting to you. We'll be visiting Iceland and Scotland as part of the deal. Meanwhile, I'll catch up on climate news and work on some key stories for next time.

For now, I'm so glad to be home to check on the progress of our little refugium in the back. There's plenty of weeding to do, but we're getting our first blooms from the Golden Alexanders. Hairy Beardtongues are not far behind.