Refugia Newsletter #36

Pilgrimage to the South, Louisiana's Cancer Alley, Black church leaders, and spring birdsong.

Refugia News

The other day, I slept with the window open a crack and woke up to birdsong! Welcome, birdies! In Michigan, waking up to daylight (instead of winter darkness) and birdsong means that winter’s grip is loosening. Then again, we did get about six inches of new snow yesterday.

Happy Women’s History Month! The good people at Fortress Press are celebrating with a 30% discount on select titles, and Refugia Faith is among them. So now might be a great time to set up your reading list for Earth Month. Or you could plan ahead for spring birthdays or Mother’s or Father’s Day gifts! This deal only lasts until March 31.

Today I’ll be headed out to Saugatuck, Michigan, for a visit with the good people of All Saints Episcopal. We’ll be reflecting on Lenten and Easter themes from Refugia Faith. These folks intimately understand the sections of the book in which I rhapsodize about the Michigan shoreline. I look forward to swooning together a bit about this place that we all love.

On March 18, I’ll be headed to Pella, Iowa, for a series of appearances. Why Pella, a little town an hour southeast of Des Moines? Because I lived there from 1992-1996 and I still have good friends there. Plus, never underestimate the cultural life of Iowa—that’s what I learned while living there. If you’re anywhere nearby, please feel welcome to show up to hear me preach on Sunday morning (!), March 19, at Second Reformed Church, or for my library talk on Sunday afternoon, or for my reading on Monday evening. Pella is a special place. My mother used to call it a “jewel in the cornfields.” True in many ways.

This Week in Climate News

Just for this week, the news can wait. Instead, as promised last time, I want to tell you about how I spent my spring break last week.

Deeper Dive

Husband Ron and I had the extraordinary opportunity to join a group sponsored by the Calvin Institute of Christian Worship on a trip to the South, an immersive study of America’s brutal legacy of racism and injustice. The trip was organized by the Institute in partnership with two excellent organizations, Telos and Arrabon. Our group of thirty people—about half of us Black, half of us White or Latinx—visited New Orleans, Jackson, Selma, and Montgomery. Wow. There’s so much to process, so much to reflect on. I’ll focus on one part of the journey, our visit to the Whitney Plantation near New Orleans, a place that not only teaches about slavery but also demonstrates the roots of modern environmental racism in the Americas.

Sacrifice zone. That’s the phrase that plagued me the whole trip. Whitney was created in 1752 as a rice and indigo plantation. Forget any images of a stately, pillared Big House or avenues of oaks draped in Spanish moss. That imagery, our guide explained, is almost entirely a fiction deliberately cultivated after the Civil War. Instead, think of modern, industrial monoculture—except there are no machines, only enslaved workers. The landowners at Whitney lived in a relatively modest house—the one we toured was built skillfully in 1790 by enslaved labor—and overseers did the dirty work of keeping the enslaved workers in line. Every inch of the place was dedicated to producing as much indigo, rice, and later sugar cane as possible. Whatever that did to people and land.

We were privileged to learn from Yvonne Holden, who has just joined the Telos team after working as Director of Operations and Visitor Experience at Whitney. The place has been carefully researched and curated to tell the real story of plantation life in the 18th and 19th centuries. As we toured the grounds and reflected on what took place there, it struck me that both land and people were enslaved together, the same abusive impulse rationalizing both enslavements. All for the sake of creating wealth for White enslavers.

The back of the plantation house at Whitney Plantation.

Yvonne Holden teaches our group near enslaved workers’ quarters at Whitney Plantation.

When it was time to process the sugar cane harvest, it was a round-the-clock operation involving huge cooking pots.

Whitney features several memorials to the enslaved workers who lived and died on the plantation. Historical records verify many of their names, but many are also unknown.

On the way to and from the plantation, we passed through the modern equivalent: Louisiana’s Cancer Alley. Louisiana is still a sacrifice zone. This is where the petrochemical industry has built miles of plants. We’ve long known that extreme air and water pollution in this region cause health problems, particularly among Black residents, whose property values have plummeted along with their health since the chemical plants moved in. But evidently, that State of Louisiana and the rest of the country find this sacrifice acceptable.

This story from 2017 by Lauren Zanolli of The Guardian sums up the background:

About ten years ago, the town [St James] was rezoned from residential to industrial, paving the way for the highly concentrated development seen today. Fifteen large industrial sites — mainly oil storage facilities, pipelines, and petrochemical plants — now fill the 13-mile stretch of road that defines the town of St James, also known as the fifth ward of St James parish.

Yet residents here say they’ve seen little economic benefit — either in jobs or tax revenues — from the industry that has taken over the town. Instead, they say, they’ve been saddled with a myriad of health issues, medical bills, and environmental degradation. [emphasis added]

Why this part of Louisiana? Location—near the Mississippi—and Louisiana’s welcoming arms:

Louisiana has developed an outsized role in the country’s energy and petrochemical industry, thanks in part to generous tax breaks that are largely borne at the local level.

The Denka plant, formerly owned by DuPont. Image credit: Bryan Tarnowski/The Guardian

Since President Biden took office in 2021, cleaning up “Cancer Alley” has become an environemental justice priority. An article by AP newswriters Michael Phillis and Matthew Daly explains that the Justice Department filed a lawsuit in February against Japanese chemical company Denka:

Denka Performance Elastomer LLC makes synthetic rubber, emitting the carcinogen chloroprene and other chemicals in such high concentrations that it poses an unacceptable cancer risk, according to the federal complaint. Children are particularly vulnerable. There is an elementary school a half-mile from the plant.

This is only one lawsuit against one company, an effort to tug on one nasty weed in a toxic garden of land- and people-abuse. The article notes:

The complaint is the latest move by the Biden administration that targets pollution in an 85-mile stretch from New Orleans to Baton Rouge officially known as the Mississippi River Chemical Corridor, but more commonly called Cancer Alley. The region contains several hot spots where cancer risks are far above levels deemed acceptable by the EPA. The White House has prioritized environmental enforcement in communities overburdened by long-term pollution. [emphasis added]

It’s all of a piece, I kept thinking. Abusing land and people, sacrificing some to secure wealth for others. The forms this abuse takes have evolved since the onset of the transatlantic slave trade in the 1500s, but it’s still the same basic story. This was a heavy thing to experience, as you can imagine.

Refugia Sighting

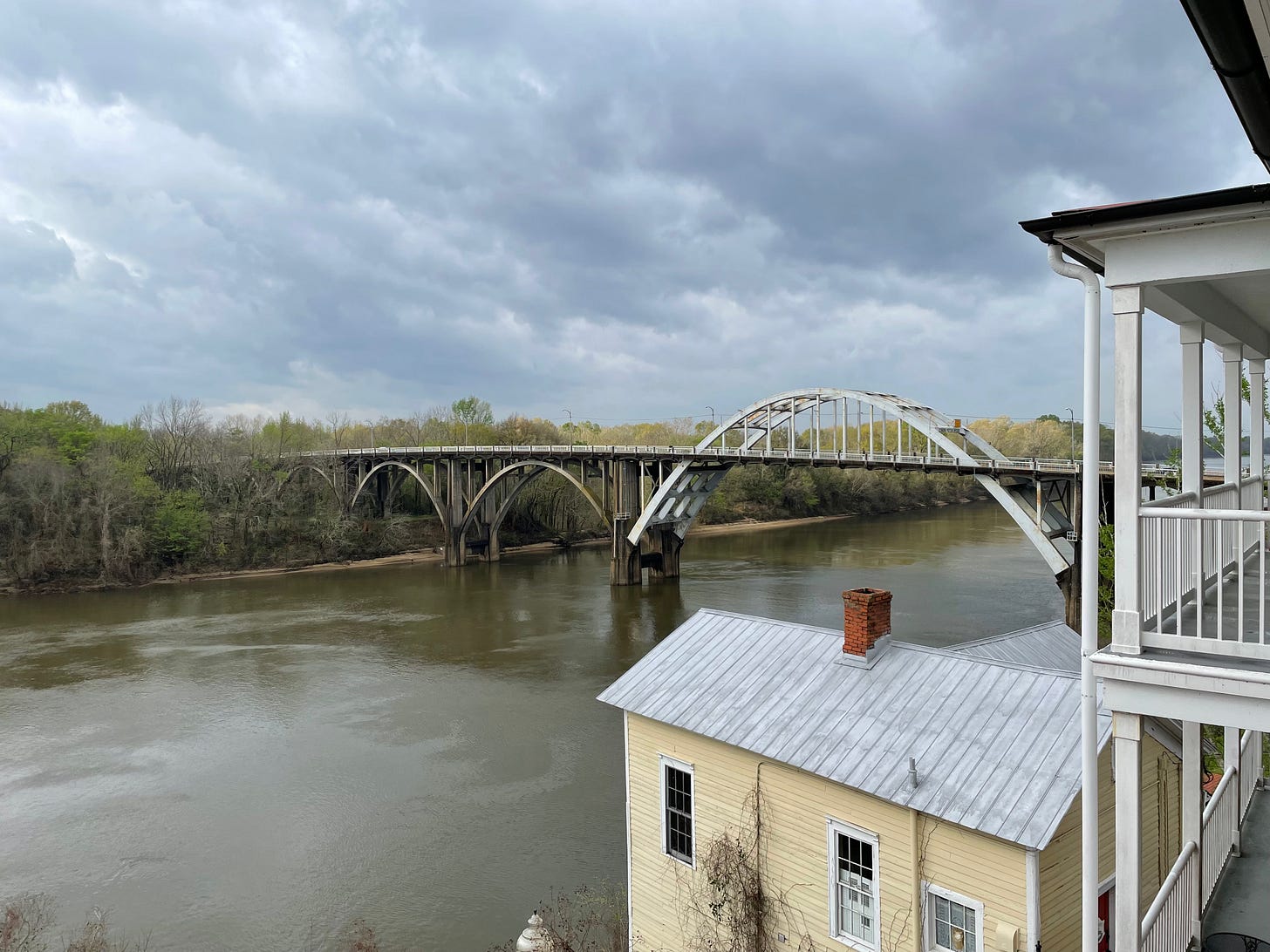

There were many heavy moments on this pilgrimage. I think especially of walking the Edmund Pettus Bridge (sorry I spelled this wrong in the last newsletter!), visiting the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum and the stunning Legacy Museum in Montgomery, visiting the National Memorial for Peace and Justice. It was especially sobering to witness the particular pain felt by our dear companions of African descent. Much of their pain simply couldn’t be spoken.

A view of the Edmund Pettus Bridge from our hotel. We walked the bridge on Saturday, the morning before the Bloody Sunday commemoration on March 5.

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice honors those 4400 Black Americans murdered in lynchings between 1877 and 1950.

In the midst of the heaviness and grief, however, we also witnessed the incredible power of Black leaders who have, since the very beginning of the transatlantic slave trade, created refugia. I think of the “hush arbors” (or brush arbors or hush harbors) on plantations, where enslaved people found moments of solace in singing, worship, and prayer. Or Congo Square in New Orleans, where enslaved people spent their Sundays dancing and trading goods and reconnecting with family—and where lively drum circles still gather on Sunday evenings. Or the Black churches of Selma and Montgomery, the beating hearts of the Civil Rights movement.

Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church, where MLK helped organize the Montgomery Bus Boycott

And I think of current leaders like Cassandra Welchlin, who convenes the Black Women’s Roundtable, an intergenerational group working at the intersections of race, gender, and poverty. These women work on policy initiatives and build leadership capacity among young Black women and girls. They are working on longterm “leadership infrastructure”—building capacities toward more stable, more thriving “ecosystems,” just as refugia should. The bill that just passed the Mississippi legislature on March 7, extending Medicaid benefits to one-year postpartum for birthing mothers, is partly down to the behind-the-scenes work of groups like Cassandra’s.

Or I think of Ainka Jackson, founding Executive Director of the Selma Center for Nonviolence, Truth and Reconciliation. This group does nonviolence training and works on so many other initiatives I can’t even list them all. They are committed to “bridging divides and building the Beloved Community.”

Even amid the most pernicious legacies of racism, injustice, poverty, and land abuse, these incredible leaders insist on creating refugia spaces and painstakingly building practical hope toward a better future. It’s one thing to know intellectually that these refugia exist, but quite another to meet the people doing the work every day.

I think all of us came home changed: lamenting, inspired, determined. I am profoundly grateful for all the people who shared their pain, their dreams, and their perseverance.

The Wayback Machine

Let’s end where we began: with birdsong. This is an essay I wrote in 2018 and much of it ended up in Refugia Faith eventually. I’ve since become much better at bird identification, and the Merlin app now has a Sound ID feature that is awesome. Highly recommend. But I still have a lot to learn.

The birds seem to be calling me out of the human-words echo chamber entirely. This comes as a relief, because whatever those birds are saying, cynical skepticism need not apply. No moral discernment needed, no political judgement. They lie not, neither are they corrupt. Their conversations are refreshingly edifying. The birds are just being birds.

Image credit: Phipps Conservatory

Till next time, be well.