Refugia Newsletter #46

Nightmare summer, migration patterns, farm refugia, and marauding dragons

Refugia News

Last weekend I was “up north”—as we say in Michigan—at the Au Sable Institute near Mancelona, helping out with “climate day” and giving a talk to some lovely students. Au Sable is a unique place where students from Christian universities come in the summer for five-week experiential courses in environmental science, taught by excellent faculty. It’s like summer camp with serious science.

In the morning, my friend Prof. Tim Van Deelen (from U-Wisconsin Madison) gave a sobering, fact-stuffed presentation on climate change, leaving everyone appropriately gloomy. In the afternoon, I tried to help students grapple with the theological ideas from their mostly conservative evangelical communities that make dealing with the climate crisis especially challenging for some young Christians. These young people find themselves torn between what they know and fear and what their communities tell them. We had to cope with spirit/matter dualism, escapist eschatology, political influences—all kinds of tough stuff. Students bravely discussed the issues and asked great questions. I think we were all exhausted afterwards!

Except for a 15-minute downpour, during which we all ran inside, we succeeded in enjoying our outdoor classroom. I also appreciate teaching in hiking pants and a tee-shirt.

Speaking of weeding out problematic things, it turns out that large native plantings require ongoing maintenance. We have a new native planting in the front, but we also have a native plant refugium area that we share with our neighbors in the backyard (written about in Refugia Faith), and this summer we were faced with an enthusiastic invasion of willow herb. So I called in the troops from Calvin University’s Plaster Creek Stewards and we worked for three full hours removing willow herb, getting after lingering buckthorn, and escorting some impressively large thistles into a big truck bed to be safely composted. The newly liberated swamp milkweed, rattlesnake master, Missouri ironweed, and coneflowers seemed much happier afterwards.

Thankfully, the Plaster Creek folks are able to send out helpers when needed, for a reasonable fee. Nothing like the power of skilled undergraduates and recent grads. That trailer is piled with all the weeds we pulled out of the native planting.

This Week in Climate News

Well, friends, I don’t have to tell you that it’s been a terrifying summer so far, and it’s not over yet. Here’s a summary from Jacob Stern in the Atlantic newsletter from July 13:

It’s getting hard to keep track of all the overlapping climate disasters. In Phoenix, Arizona, the temperature has broken 110 degrees for nearly two weeks running. The waters off the Florida coast are approaching hot-tub hot, and before long, marine heat waves may cover half the world’s oceans. Up north, Canada’s worst wildfire season on record burns on and continues to suffocate American cities with sporadic smoke, which may not clear for good until October. In the Northeast, floods have put towns underwater, erased entire roadways, and left train tracks eerily suspended 100 feet in the air. Also, the sea ice in Antarctica—which should be expanding rapidly right now, because, remember, it’s winter down there—may be losing mass.

This summary doesn’t even mention the terrible heat in Mexico, Europe, and China. We are now depressingly familiar with terms like “tipping points” and “new normals.” As I mentioned in the last newsletter, the El Niño cycle is exacerbating underlying climate shifts, and will continue to do so for 18 months or more.

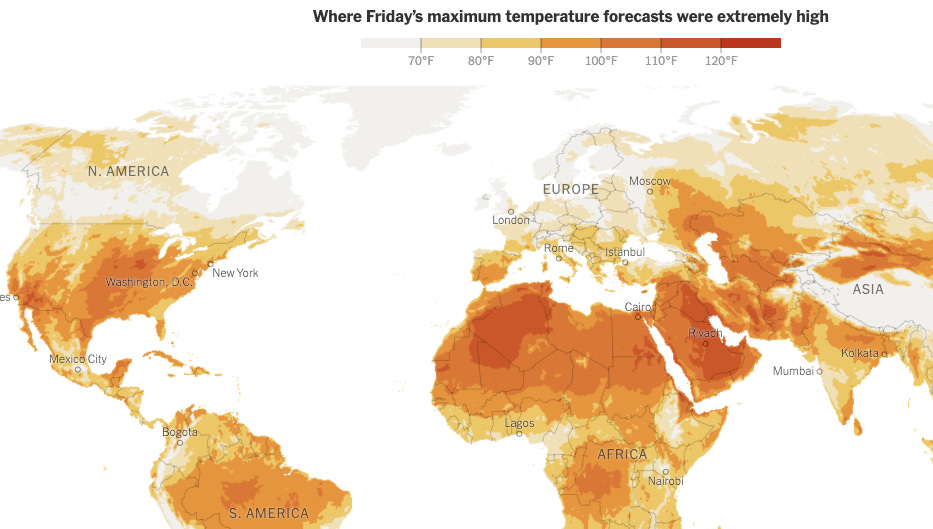

The map below was updated July 28.

Image credit: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2023/world/global-heat-map-tracker.html

In the midst of all this, it is especially important not to succumb to “doomism.” So I have two suggestions for us all this week.

First, read this article by Rebecca Solnit from The Guardian. Solnit argues that, while it’s fine to feel your feelings, settling into “doomism” is dangerously self-defeating. Moreover, doomism is often based on old or bad information.

Many things that were once true – that we didn’t have adequate solutions, that the general public wasn’t aware or engaged – no longer are. Outdated information is misinformation, and the climate situation has changed a lot in recent years. The physical condition of the planet – as this summer’s unprecedented extreme heat and flooding and Canada’s and Greece’s colossal fires demonstrate – has continued to get worse; the solutions have continued to get better; the public is far more engaged; the climate movement has grown, though of course it needs to grow far more; and there have been some significant victories as well as the incremental change of a shifting energy landscape.

We know what to do. We have the solutions. Yes, it will be hard. But every tenth of a degree counts. Therefore, as Solnit concludes, “fighting defeatism is also climate work.”

The second thing I would recommend is to follow a reliable content creator focused on good news. I know I need this. There are great creators out there. I am fond of Alaina Wood. I follow her on TikTok but you can find her elsewhere. She is also involved in the Pique Action newsletter, which you can find here.

Finally, I promise to offer at least one encouraging story or fact in every newsletter. We need to celebrate victories to keep us going. The Solnit article is this week’s.

Deeper Dive

If you have been directly affected by the wildfires, heat, and flooding this summer, you might be wondering: should I move? That question will become more common and, for many people, more desperate as the climate shifts—even under best case scenarios. Climate migration is already a global reality and will continue to accelerate. The question is: can we prepare well to cope?

The New York Times Magazine and ProPublica joined with the Pulitzer Center in 2019-2020 to do a huge, three-part series on climate migration. The articles, written by Abrahm Lustgarten, are worth revisiting. One of the themes of the articles is that it’s difficult to make projections about human migration for many reasons, partly because human behavior is difficult to predict and partly because so many variables are involved. However, the modeling processes are getting more sophisticated. In any case, the message of all three sections is the same: we must prepare. As Lustgarten writes:

Should the flight away from hot climates reach the scale that current research suggests is likely, it will amount to a vast remapping of the world’s populations.

That is not going to happen without conflict and suffering. Whether or not countries and cities engage in realistic preparation will help determine how much.

The articles note that people generally do not want to move. Globally, when it comes to climate migration, they move because their crop lands fail or because of sea level rise and flooding. Rural people tend to move first to cities, which can stress infrastructure and crowd people into slums. Only if necessary do people want to move across borders. And we can expect this:

As their land fails them, hundreds of millions of people from Central America to Sudan to the Mekong Delta will be forced to choose between flight or death. The result will almost certainly be the greatest wave of global migration the world has seen.

The articles suggest that “hardening borders” is only going to cause more suffering. But how to manage flows of people from areas of the earth that will no longer support farming, cities, and human communities? The U.S. will of course have to be more realistic about migration than has been politically possible so far.

El Paso, Texas, for example, has received a large number of migrants from Central America, but is having its own resilience problems because of much hotter temperatures. They have tried to address climate migration intentionally:

In 2014, El Paso created a new city government position — chief resilience officer — aimed, in part, at folding climate concerns into its urban planning. Soon enough, the climate crisis in Guatemala — not just the one in El Paso — became one of the city’s top concerns.

Even apart from cross-border migrants, will more Americans start moving from hotter, floodier, stormier, fierier regions of the country to other regions of the country, seeking out “climate havens”? Well, as the article points out, Americans tend to be less desperate and therefore even more reluctant to move:

By comparison, Americans are richer, often much richer [than the global average], and more insulated from the shocks of climate change. They are distanced from the food and water sources they depend on, and they are part of a culture that sees every problem as capable of being solved by money.

What happens, though, when you can no longer insure your home and people start moving out of your neighborhood and suddenly the value of your home declines? How long do you wait before you can’t sell that home to anyone and you lose its value? This is a real question for people along coasts and in places plagued by fires. And when Americans and other relatively well-off people are already stressed by climate change, how generous will we be to those who are much poorer and much more desperate?

The world can now expect that with every degree of temperature increase, roughly a billion people will be pushed outside the zone in which humans have lived for thousands of years. For a long time, the climate alarm has been sounded in terms of its economic toll, but now it can increasingly be counted in people harmed. The worst danger, Hinde warned on our walk, is believing that something so frail and ephemeral as a wall can ever be an effective shield against the tide of history. “If we don’t develop a different attitude,” he said, “we’re going to be like people in the lifeboat, beating on those that are trying to climb in.”

We’re only talking here about humans. How wildlife and plant populations might shift around is a whole ‘nother bunch of topics. Thanks to my friend Avery Davis-Lamb for sending along this cool data viz from The Nature Conservancy. It’s one model of how mammals, birds, and amphibians are likely to move—roughly speaking. Click around on the website to see how the data was aggregated and analyzed. The animation is pretty neat.

Refugia Sighting

A few weeks ago at the Wild Goose Festival, I sat and chatted for a while with some folks from an exemplary refugia space called Spring Forest in Hillsborough, North Carolina. Here’s how they describe themselves:

Spring Forest is the home and farm of the Church at Spring Forest, a United Methodist new monastic, missional faith community. Our ministries focus especially on regenerative farming, supporting refugee resettlement, contemplative and healing spirituality, and fostering the nutritional and spiritual well-being of our neighbors.

Image credit: springforest.org

Several families live on the farm at the “Farmastery.” Lots of people in the dispersed community of Spring Forest friends help with the regenerative farm, which provides produce for a CSA as well as for food donations. They have potlucks, contemplative spirituality gatherings, educational programs for families, and more. Plus sheep, goats, chickens, and ducks.

Healing and hospitality for refugees is a central value for the community:

Our international friendship garden, under development, is especially designed for immigrants who long to grow familiar vegetables in their new geographic context. Along with garden space and mentoring from our farmers and volunteers, our program offers hospitality, friendship, and support with cultural adjustments for our new neighbors.

The Spring Forest folks have figured out one excellent, refugia-oriented way to prepare for climate migration: create resilient communities that make intentional space for welcome.

Thanks to Deborah Coble and Sheryl Taylor for sharing their Spring Forest stories with me, and to Ben Yosua-Davis for recommending that I visit Spring Forest’s table at “the Goose.”

The Wayback Machine

After all that seriousness, here’s something silly. We’re in the middle of summer (at least in this hemisphere), which means that churches are in the middle of “Ordinary Time.” Ordinary Time is that long stretch between Pentecost and Advent. That’s a lot of weeks of church life with nothing special going on, liturgically speaking. So, to mitigate the doldrums, in 2019 I came up with some suggestions: “Let’s Make Ordinary Time Extraordinary Again.” Here’s a taste:

Weird prophet season

Prophets and their oddball ways do not get enough love in the traditional liturgical year. Apart from a few juicy Isaiah quotes in Advent, how often do we incorporate plumb lines and ax heads, head-shaving and jar-smashing into worship? Lots of related craft project opportunities, including the chance for the high school youth group to graffiti ominous warnings on the walls.

Check out the piece for more on “Apocalypse Season” and a brief appearance from the dragon in Revelation.

(Note: Unless otherwise indicated, any bold print in quoted material in this newsletter is added.)

I hope you are finding encouragement and strength, whatever challenges you are facing. Till next time, be well.

Very much appreciate the counsels of this letter, especially away from doomism. I have a friend who's denying, not climate change, but human culpability for it. I suspect that doomism doesn't help in conversations with folks like that. Appreciate the pics, too. Great content.