Hello, friends. Today we’re going to hold off on our usual climate news dump/commentary because I’m here at the Festival of Faith and Writing, right here on my campus at Calvin University. The Festival is a “three-day celebration of literature and belief”—basically a three-day book party with big, open doors and a big heart.

I have been involved in Festival planning and hosting in one way or another since 1998—the biennial event started in 1990—and I love doing this work with my colleagues. We haven’t held an in-person, on-campus Festival since 2018 because, you know, Covid. So it has been absolutely wonderful to welcome 80 writers and some 2000 attendees to campus.

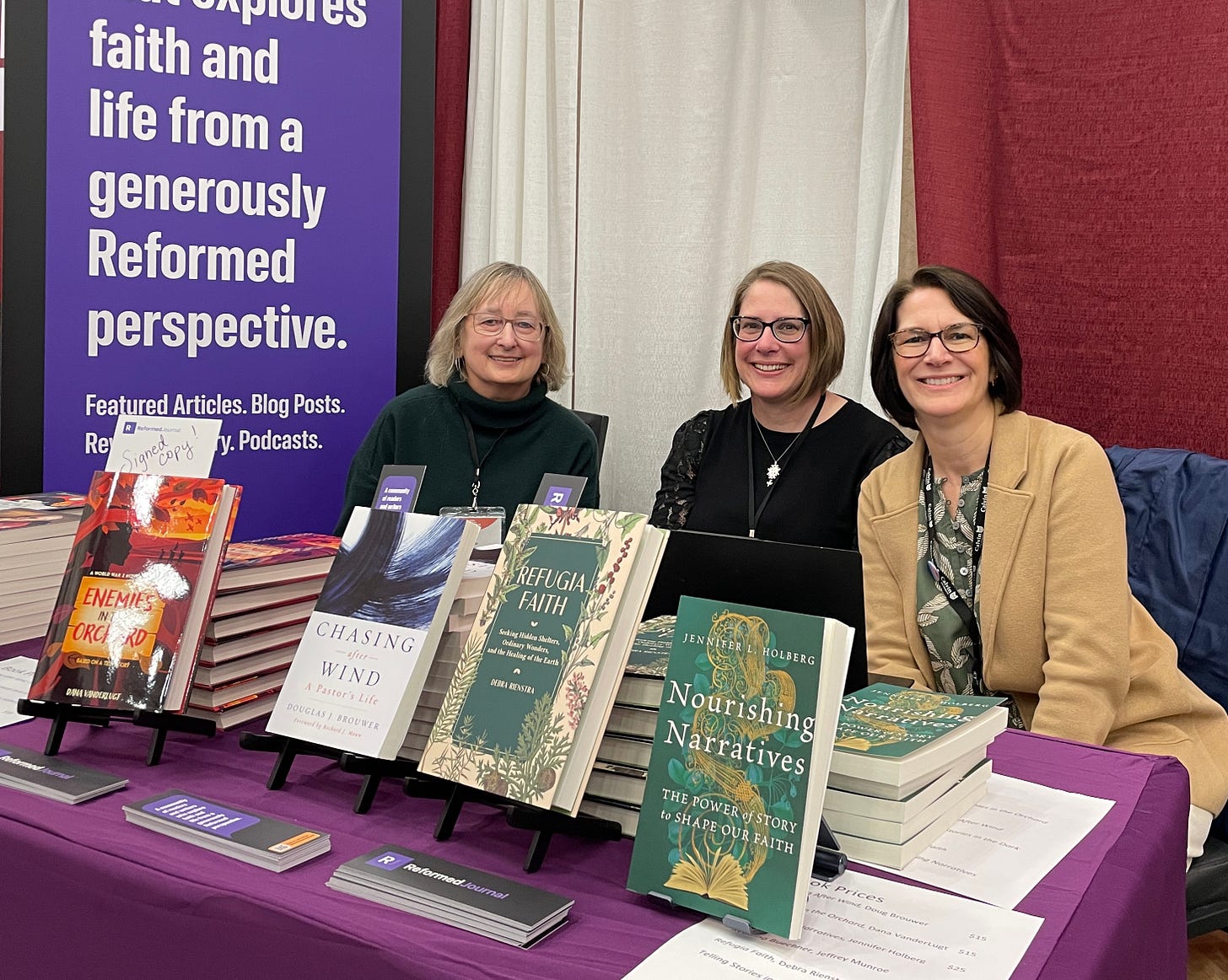

Reformed Journal, the online magazine where I write on the weeks I’m not writing this newsletter, has an exhibit table at Festival, and they have been kind enough to sell copies of Refugia Faith at the table. Pictured L to R are Laurie Orlow, an RJ board member; Rose Postma, our poetry editor; and me. Thanks to Steve Orlow for this photo.

I’m in deep with Festival fun all weekend, so I hope you won’t mind if I feature two quick, Festival- and ecology-related items this time. (We’ll go back to our usual format on April 27.) First, a few thoughts from a great session yesterday morning on the “ecological imagination,” and then some artwork from an ecology- and refugia-related art exhibit now showing in our campus art gallery.

The Ecological Imagination

Yesterday, I got to moderate a rich conversation between an old friend, Fred Bahnson, and a new friend, Matthew Dickerson. Fred writes masterful essays about ecology and spirituality. His essays often take the form of high-craft immersion journalism. In Refugia Faith, I quote from his piece on the church forests of Ethiopia—an essay that continues to inspire me. Meanwhile, Matthew writes historical and fantasy fiction and also has two important books on ecological themes in C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien.

We chose “the ecological imagination” as our theme and spent some time considering how this moment in history calls for reshaping our ways of thinking—and thus doing—and how important literature can be for that reshaping process. Apparently, people are very interested in this topic. Our session was packed, and the audience seemed eagerly engaged.

Matthew spoke of the ecological imagination as a matter of “seeing complex fabrics” and Fred described how, since “ecology is the study of relationships,” fiction and nonfiction can help us enter “proximity to and relationship with the more-than-human world.”

Fred Bahnson with his student guide, Esther Jun. All our guest speakers are assigned an intrepid Calvin student to help them get from place to place on campus. Our students are crucial to making the Festival run smoothly.

In both fiction and nonfiction, we acknowledged the importance of narrative since, as Matthew put it, “stories and character capture our imagination” and it’s often “the stories that motivate us to act.” Matthew noted that Tolkien, in the Lord of the Rings trilogy, “spends more time writing about plants and animals and food and community than actually writing about battles and action.”

This led to a very interesting discussion of heroism. Because we are in many ways a film culture, and film thrives on action and sensation, we are saturated with stories of heroes who “win” through action, usually violent action, and often domination. Yet, an ecological vision invites us to consider other kinds of heroism, other kinds of winning.

Matthew gave an example from Tolkien, suggesting that the “greatest hero in Tolkien’s Middle Earth work maybe is Faramir,” a character who is not merely a courageous battle hero, but one who “cares about bringing healing to a wounded earth.”

I suggested that perhaps this moment in history demands that we imagine the heroism of working together, and Fred brought to bear some examples from his book Soil & Sacrament, in which he paints in-depth portraits of faith communities who focus on combining a life of prayer with growing food—Trappist monks, a Jewish farm community, and a church community garden, for example.

Of course, the “writerly challenge” here is that when it comes to storytelling, fiction or nonfiction, we still have a need to follow individual characters. So as writers, we have to go through individual stories in order to show how heroic community might look and feel.

We also had an interesting discussion on ecotones, that is, places where ecosystems overlap—edge places. These are typically the most fecund, biodiverse, and lively places in nature. We wondered if we might be at an edge place in history, between one era and the next, a time of upheaval but also of great richness. And perhaps new forms and patterns in literature are especially apt for such a time. Fred advocated for “putting yourself in uncomfortable situations” as a great “writerly challenge”—perhaps leaning into those cultural and interpersonal edge places.

Naturally, our most admired writers came up. Barry Lopez made an important appearance, and of course Wendell Berry, too. One of Fred’s favorite Berry quotes: “It was the desert not the temple that gave us the prophets.” The audience clearly appreciated that one. And Matthew cited Robin Wall Kimmerer and the crucial dictum that “all flourishing is mutual.”

I felt that we had only begun this conversation, one that involves not only artists and writers but all of us. How do we use the power of the arts to help us negotiate a reality that calls for communal courage and a commitment to mutual flourishing? That question will remain an ongoing challenge, and I’m grateful for partners like Fred and Matthew in working on that challenge together.

Art about Inhabiting and Connection

Artist and friend Jo-Ann Van Reeuwyk is recently retired from the faculty here at Calvin. Apparently, her latest work was influenced by Refugia Faith? That’s what she tells me anyway, and I’m so pleased that the refugia concept has been generative for her. (I interviewed her on my podcast back in the day, too.) As you know if you are a regular reader here, I’m a big fan of artists who use their mode of knowledge and expression to help us develop those ecological imaginations we need.

Jo-Ann and her friend and fellow artist Jen Boes have collaborated to create an exhibit called “Inhabiting: Seeking Connection.” The mixed-media exhibit explores mapping, topography, and the ways we inhabit places. Their finished work is paired with an interactive station where visitors can make their own pieces.

I’m in love with Jo-Ann’s series of images like this one, featured in the exhibit. Jo-Ann is thinking of neurons and tree-branching, but these images also remind me of the mycorrhizal networks under the soil. Not a coincidence, of course. These patterns are embedded in nature’s fabric.

Here’s what Jo-Ann says about the show:

We explore physical and spiritual interconnectedness, disconnectedness, and belonging through the interweaving of paint, dye, paper and cloth. Here is a shared human experience in the inhabitation of spaces and places: the physical and the immaterial, the intimately known and the unfamiliar. On our journey through these territories, what does deeply inhabiting look like? How does our connectedness alter, re-define, construct and break down these realities?

Two more of those branching pieces, titled “Soliphilia” and “Emergent,” plus a fiber work by Jen Boes called “Tenuous Hold.”

Here’s more from Jo-Ann:

What began as a love for mapmaking and in particular the symbolism in Aboriginal mapping has morphed into a study of topology and how topology itself is repeated both in situ and ex situ. Here we try to provide dialogue between artists, between art pieces, and within community. But we also try to provide a type of sanctuary, a place and space to think, to be, to create, to connect, to pray. We hope this space provides a type of refugium for the visitor prompting participation and interconnectivity. From mapping to interior brain activity, to honoring our spaces and habitation with all of nature, from internal structures to creating connectivity between them, ultimately we suggest soliphilia: a love for the completeness of our inner and outer spaces.

Detail from “Tenuous Hold” by Jen Boes

That term soliphilia is so useful. It was coined by Glenn Albrecht, an Australian philosopher who is trying to find new words to describe feelings arising in this time of climate crisis. Soliphilia is the energizing love that we so urgently need right now, a love that drives us to care for and heal our beloved places.

All right, I’m headed back into the fray. Fred is doing another session this morning and the whole thing winds up this afternoon with a plenary talk by Anthony Doerr, author of Cloud Cuckoo Land and All the Light We Cannot See. If you are now jealous, and you probably should be, please join us for the next Festival in spring of 2026!

I’ll be back next time with the usual format. Till then, be well.

As usual, all bold text in quotations is added.